Contents

The Foundation: A Learning Culture

‘A learning culture is a set of organizational values, conventions, processes, and practices that encourage individuals—and the organization as a whole—to increase knowledge, competence, and performance.’ (Seven Steps to Building a High Impact Learning Culture, Oracle Human Capital Management)

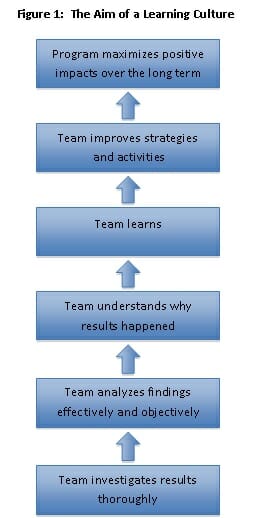

Experience has shown that a learning culture is the foundation of a results measurement system. It is fundamental to a program’s ability to use information on results to improve program strategies and implementation as well as to report results credibly. With these aims as its focus, the DCED Standard strongly supports an effective learning culture. In the complex environments in which private sector development programs work, adaptive management is essential. A program must gather information on what is happening in the field, analyse that information to understand observed changes and why they are happening, and use those insights to improve strategies and implementation. This process, which is embedded in the DCED Standard framework, enables a program to maximize long-term, positive impacts with the time and money available. A learning culture provides the incentives and structure for this process to happen effectively. Conversely, experience has shown that, without a learning culture, even the most technically sound results measurement system is unlikely to be effective in generating credible results and enabling managers and staff to use information on results to improve implementation.

For the purposes of this paper, a learning culture:

- encourages staff members to gather thorough information on market systems and on results;

- supports staff members to analyze the information objectively, with an eye towards understanding what is happening and why, rather than confirming pre-conceived ideas;

- motivates and enables staff members to use information on market systems and results to improve strategies and activities.

Figure 1 illustrates the aim of a learning culture for results measurement. Building a learning culture in a program is not easy.

In many programs, there is pressure to get things done quickly and to reach short-term targets, often leading to a premium on acting, rather than analysing and adjusting strategies to maximize long-term impacts. Hierarchical organizational structures can encourage silos, where individuals or small groups work in isolation, rather than interacting and sharing lessons with others. Program managers and staff understandably get attached to their work – making it more difficult to interpret information on results objectively.

This case describes the experiences of the Market Development Facility (MDF), which applies the DCED Standard, in creating and maintaining a learning culture. It defines the key attitudes and practices that are essential to MDF’s learning culture. It explains what MDF has done to promote those attitudes and practices, focusing on practical tips and examples on what has worked for MDF. Finally, it discusses external influences on MDF’s culture and how the program has managed them. The heart of the case is a series of interviews conducted with MDF managers, staff and donor, where they describe in their own words the MDF organizational culture, how it works, how they have developed it and how it benefits them and the program. Click on the links in each section to view the interviews.

Introducing the Market Development Facility

MDF is a multi-country, private sector development program funded by the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and implemented by Cardno Emerging Markets. MDF’s goal is to create additional employment and income for poor women and men in rural and urban areas through sustainable and broad-based pro-poor growth. To pursue this goal, MDF negotiates partnerships with strategically positioned private and public sector organizations. The partnerships aim to support innovative ideas, investment and regulatory reform that will increase business performance, stimulate economic growth and ultimately provide benefits for the poor – as workers, producers, and consumers. MDF currently works in Fiji, Timor Leste, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea and Sri Lanka. This case focuses mainly on the program in Fiji. To learn more about MDF, see the MDF website.

MDF started working in Fiji in July 2011 and the current phase of the program is scheduled to end in 2017. With a budget of AUD 8.8 million, MDF in Fiji aims to create approximately 1,100 jobs and increase incomes for 12,000 households, reaching up to 67,000 women, men and children. More broadly, MDF aims to catalyse changes in the Fiji economy that will underpin inclusive growth over the long term. To achieve this, MDF works in sectors that represent a major part of the economy, have long-term growth prospects and are relevant for poverty reduction. The two initial sectors chosen in Fiji were horticulture and agro-exports, and tourism and related support services and industries. Later, export processing was added into the MDF Fiji portfolio. At the time of writing, MDF had 33 on-going and three completed partnerships in Fiji.

MDF’s multi-country operations are steered by a Core Leadership Team. This team consists of a Team Leader, Results Measurement Manager, Communications Manager and a Country Representative for each country. Fiji’s Country Representative is also the Deputy Team Leader for the Facility. Click to see an organogram of the multi-country structure.

A Country Implementation Team implements the program in Fiji with support from the Core Leadership Team. This Country Implementation Team is composed of 13 staff members working on implementation and two support staff, led by the Country Representative. The majority of the implementation staff members are business advisers who manage interventions in MDF’s three target sectors. The business advisers are supported by two results measurement specialists and led by a team coordinator. The MDF Fiji team members are all based in one office in Suva, the capital. Click to see an organogram of MDF in Fiji.

The Challenge of Building a Learning Culture in MDF

MDF had a number of things in their favour when building a learning culture.

- A flexible program design. MDF’s program design provided flexibility and emphasized that the program should learn and improve based on regularly-measured results. The design explained the program’s approach and set down some impact level targets but left the strategy and tactics to be developed and improved by the implementers.

- An emphasis on learning. As MDF represented a relatively new approach for DFAT, there was an emphasis on learning from the start, which extends to the donor as well as the program.

- Requirement of the donor to comply with the DCED Standard. MDF developed their results measurement approach and processes based on the DCED Standard from the very beginning. The DCED Standard not only addresses technical elements related to measurement but also emphasizes understanding and using results measurement as a management tool.

- A supportive national culture. Fiji has a culture that is open and friendly, with a focus on building relationships.

However, MDF still had a number of challenges to building a learning culture. Some of these are common to many programs while others are unique to MDF.

- The market development approach in Fiji is new. Before MDF started, there was little experience with a market development approach in Fiji. Consequently, the business advisers had to learn the approach from the beginning. Most of them had not experienced the flexibility associated with the approach before and none had been exposed to the frameworks that help practitioners make sense of the information they find in markets. Therefore, time, effort and coaching were needed for the business advisers to fully grasp the approach and be able to effectively learn and adapt strategies and interventions.

- It was easy for silos to creep into MDF’s work. Like many programs, MDF had to contend with the tendency of organizations to gravitate towards silos. There was a tendency for business advisers to focus on ’my sector.’ In addition, with so much to think about early on, there was also a tendency for business advisers to think that results measurement was not their responsibility but the responsibility of the results measurement staff.

- There was pressure to get interventions going. Even though MDF has flexibility, the program still experiences the common pressure to get interventions going. Many markets are thin in Fiji and it can be challenging to find capable companies with innovative and potentially pro-poor ideas. Consequently, as with many programs, there is a tension between the time available for thinking and the time available for doing.

- Fiji’s hierarchical social structure can discourage debate. Fiji’s social structure encourages people to be polite and for some groups to defer to others. For example, in Fiji young people are generally expected to defer to older ones. This can make people cautious in bringing forward their ideas or disagreeing with others.

Building a Learning Culture in Practice

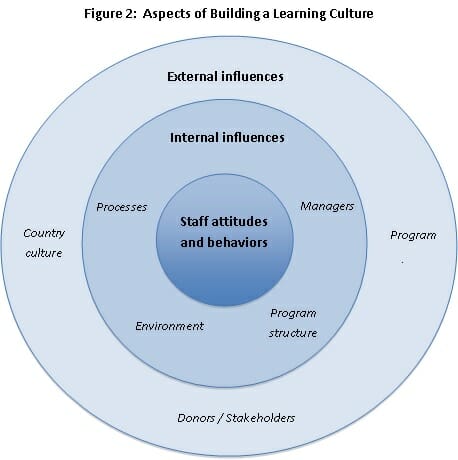

Staff members’ attitudes and behaviours are the core of a learning culture (See Figure 2). These include not only how each staff member acts, but also how they interact with each other. Both internal and external factors influence this core. The most important of these influences is managers’ behaviours. Other important internal influences are the structure of the program, the physical environment that the team works in and the management processes and tools that guide the work. External influences on the organizational culture are the original program design, donor and stakeholder support and the culture of the country. Managers must address the ways in which these factors influence the program’s learning culture.

Click on the image to see Shahroz Jalil, MDF Fiji Country Representative, discuss his aims for, and experience with, MDF’s learning culture.

Staff Attitudes and Behaviours

The MDF team describes the following attitudes as central to a learning culture:

- Humility: to be able to learn, a person must understand and admit that s/he does not know things. A lack of ego also makes a team member more likely to ask others for help and makes him or her more pleasant to work with.

- Program focus: a central value of MDF staff is maximizing the positive long-term results of the whole program. This means that each team member is guided by what is good for the whole program as opposed to what is good for his/her own interventions or advancement.

- Valuing teamwork: many MDF staff members emphasize the importance of teamwork to learn and achieve the best possible results. It is clear they value teamwork and how it can improve ideas and practices. • A passion for learning: MDF staff members are required to learn about different sectors, different people and new ways of working. It is critical that they have a passion for discovery and learning.

- Inquisitiveness: MDF staff members have a genuine interest in understanding what is happening in the field and why. They want to know if interventions are working and why or why not. This attitude helps to counteract the natural tendency to see results in a positive light.

Click on the image to see Dharmen Chand, MDF Business Adviser, discuss what helps him learn and how the organizational culture affects work at MDF.

- Scepticism: the MDF team emphasizes that building an understanding of market systems and program results requires being sceptical that any one source presents a complete and objective picture of a situation. Their scepticism encourages them to be thorough and to look at findings from different angles.

- Adaptability: because MDF team members take on a variety of roles and responsibilities, they have to be willing to get outside of their comfort zone and adapt to new situations and responsibilities. The team also emphasizes that they have to be open to constructive criticism and improving the way they work.

- Objectivity: some people call this a ’spirit of honest inquiry.’ It embodies a commitment to gathering and analysing findings as objectively as possible with the aim of understanding what is happening, rather than confirming a pre-conceived idea.

| Tip: The ‘Waiter Test’ One MDF Manager recommended observing how a person treats a waiter (or driver or cleaner) to determine if they respect people regardless of their status and if they are interested and able to interact with various types of people. |

- Interest in and respect for all types of people: for fieldwork to be effective, MDF team members have to interact with a wide range of people, such as business owners, farmers, government officials and labourers. They approach this interaction in a spirit of inquiry and respect.

- Commitment: the ability to gather thorough information, analyse it objectively, report on it clearly and use it effectively to improve program implementation is not gained over night. Gaining this ability takes time and concerted effort. Passion and commitment help to sustain the required effort.

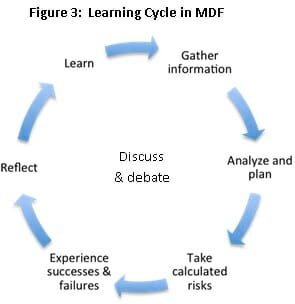

At the heart of MDF’s learning culture is a cycle of behaviors that help the MDF team to learn and improve. This cycle is represented in Figure 3. While this cycle takes different forms at different levels, the most obvious is the intervention level.

At the heart of MDF’s learning culture is a cycle of behaviors that help the MDF team to learn and improve. This cycle is represented in Figure 3. While this cycle takes different forms at different levels, the most obvious is the intervention level.

To design an intervention, business advisers gather information, for example on potential partners, incentives and innovations in the market. They analyze the information and discuss how to design an intervention that will result in pro-poor growth in light of the findings they have. They then work with a potential partner to design a partnership agreement that lays out how MDF and the partner will work together. For MDF, each partnership agreement contains calculated risks in terms of how much and what kind of support is needed to enable the partner to adopt an innovation, whether the partner has sufficient incentives and capacities to adopt the innovation and if the innovation will result in the expected income and jobs for poor people. As with any program, some interventions work and some do not, based partly on the teams’ analysis and work with the partner and partly on factors in the partner and the market.

During and after the intervention, the team reflects on what is going well, what isn’t and why, as well as how that links back to their analysis, intervention design and work with the partner. This reflection forms the basis of learning where team members internalize lessons about what works best to generate pro-poor growth. There is a consensus in MDF that generating sustainable pro-poor growth is no easy task. Staff members need to iteratively think, discuss, act and think again. Therefore, at the center of this cycle are frequent discussions and debates that enable the team members to revise and refine their understanding over time.

MDF has fostered key behaviors among the staff, based on the attitudes above. Together with the learning cycle, these behaviors define the norms of the organization.

- Work in teams. Most of the work in MDF is done in groups. For example, a results measurement specialist leads a group of four or six business advisers to conduct specific results measurement studies in the field. Everyone in MDF acknowledges that if a colleague asks for help to develop an idea or intervention, you find time to give him/her your help, not necessarily immediately but within a reasonable timeframe. This way of working felt artificial to some business advisers early on. However, it is now ingrained as a norm that they appreciate because of the valuable ideas and input they get from their colleagues which strengthens their own capacities and implementation overall.

- Go to the field often. MDF team members spend a lot of time in the field, observing markets and talking with market players. They are careful not to rely on any one source for information as they realize that any source presents only a part of the picture. Secondary sources and individual resource persons can be prone to generalizations. Any individual market player will emphasize his/her perspective. Instead the MDF staff members go out in the field regularly to gather information, float ideas and test assumptions. This firsthand view enables them to get a solid understanding of complex changes and their likely links to interventions, as well as motivating them to use information to improve interventions.

Click on the image to see Ritesh Prasad, MDF Results Measurement Specialist, discuss how the sector and results measurement teams work together.

- Tackle problems. There are always problems to address in programs, such as a partner not fulfilling the partnership agreement or a new constraint in a sector. The norm in MDF is to discuss and tackle these problems as they arise, rather than to ignore them or to try to handle them alone. Problems are a frequent topic in MDF’s regular meetings. But staff members do not wait for meetings to flag problems. They raise them as they arise with colleagues and managers and address them on a daily basis.

- Assess results. Everyone in MDF is involved in results measurement. Each business adviser recognizes that understanding the results of interventions, and reporting and acting on those findings is an integral part of his or her job. The sector teams seek out assistance from the results measurement team early in the design of an intervention and ask their advice regularly throughout an intervention life cycle. The results measurement team supports the sector teams to refine their interventions, gather information and analyze results objectively, report and use the information to improve. The results measurement team involves the sector teams in all aspects of results measurement and supports them to improve interventions. Thus, results measurement is the key mechanism through which the whole team learns and improves.

Internal Influences on MDF’s Culture

Managers’ actions are the most important factor in the development of a learning culture. Also important are the organizational structure, physical environment and management processes in the program. This section discusses how MDF has used these internal influences to shape its organizational culture.

Managers’ Behaviour

Leadership is critical to the development of a learning culture. This leadership is manifested in managers’ actions. This section highlights some of the managers’ actions in MDF that were important in the development of the organizational culture in the program. It covers shaping the team, structuring the work, setting expectations and providing support, establishing a constructive atmosphere in the program and building staff members’ competence over time.

Shaping the team

The team members are the most important factor in the success of the program and are critical to the development of the organizational culture. MDF puts considerable focus on hiring business advisers with the attitudes described above. In addition, MDF looks for applicants with high intelligence. Markets are complex and fostering pro-poor growth is challenging. Making sense of findings on markets and results, and using insights to make concrete improvements requires raw intellect and analytical capacity.

During recruitment, the managers not only consider individual attributes but also how the team will fit together. For example, in market development, entrepreneurial thinking is essential to generate ideas and spot potential connections that may not be obvious. Analytical thinking is also critical to methodically think through and shape ideas and to critically analyze information on results for the lessons they contain. A balance of these abilities is needed and may often come in different people.

| Tip: Group Discussions as part of recruitment As part of the recruitment process, MDF puts applicants into groups for the discussion of challenging issues. They then observe how the applicants discuss. Do they contribute their ideas? Do they value problem solving over making themselves look good? Do they listen to others and adopt others’ good ideas? Do they make connections and learn from others? |

In addition, MDF managers have found that hiring a mix of people with different backgrounds promotes learning. People have different perspectives. They see different aspects of problems and are able to find different kinds of solutions. A mix helps improve everyone’s capacity and generates more and more effective solutions. To attract a mix of people, MDF purposefully advertises positions in a range of publications and through a variety of networks.

While recruitment is critical, MDF has found that it is equally important to continue shaping the team once they are hired. To make a diverse mix work, managers encourage respect for different skills and viewpoints in the team. They point out how people can learn from each other and keep an eye on the balance of the team to ensure some perspectives are not dominating others. They also look out for any weak areas in the team as a whole. For subsequent hiring, they particularly look for applicants who will address weak areas and are likely to work well with the rest of the team. The MDF managers also emphasize that it is important to address conflicts in the team or behaviors that are not adding to the learning culture at an early stage. Letting things go unaddressed can undermine the entire culture of the team.

Structuring the work

The MDF managers put the country team at the core of implementation. It is the team which designs and implements the interventions. Consultants are brought in when needed to guide, support and build the capacity of the team, or to provide specific expertise, but not to do the work of the team. This enables the program to build up a team, over time, which has deep knowledge of the market systems and experience of applying market development processes and tools. Through interaction and involvement, they improve their abilities to effectively gather and use information on results. Because the team is responsible for interventions from design through to assessment, analysis and application of lessons to new interventions, they are motivated to use information to understand the results of interventions and to improve.

| Tip: Encouraging Fieldwork To encourage fieldwork, MDF makes it easy. The approval process for field visits is simple and there is usually sufficient transport available to take team members where they need to go. |

The MDF managers structure work to reinforce the attitudes and behavioral norms discussed above. To establish and reinforce the norm of frequent fieldwork, the MDF managers involve themselves in the fieldwork and analysis as well. They ask questions about the market situation and how interventions are going, both to increase their own understanding and to emphasize that business advisers are expected to thoroughly understand their sector and interventions. When business advisers are not sure about a particular aspect of the market, managers encourage them to go and find out through discussions with market players. When business advisers have answers to their questions, managers then ask them where they found the information. If information comes from the field and is well-triangulated, then managers praise the business adviser. Where the information relies only on secondary sources and/or is not well triangulated, they encourage them to gather additional information from market players.

To promote teamwork, MDF managers structure much of the work in groups. Business advisers conduct field visits in pairs. When they return, managers encourage them to discuss new findings with their colleagues. When a business adviser comes up with an idea, managers require that s/he discuss it with a group to develop the idea before presenting it.

Tip: Scrums

To promote frequent discussions among the team, MDF introduced ‘scrums.’ The term ’scrum’ comes from rugby. It’s a formation where the rugby team members are packed closely together with their heads down as they work together to gain possession of the ball. ‘Scrums’ are now used as a business management tool to help managers complete complex projects by improving teamwork, communication and coordination. MDF borrowed from this practice by introducing frequent, short team meetings to discuss progress and coordinate work. In MDF, the term has evolved to describe any short meeting to discuss an idea, finding or intervention. Click on the image to see what a scrum looks like and hear Dharmen Chand, MDF Business Advisor, describe how they were introduced and how they have evolved.

Setting Expectations and Providing Support

In MDF, managers lead by example, visibly taking on the organizational culture and behaviors they aim to promote. Most importantly, managers involve themselves in all of the program processes. They go to the field with the team and work with them to gather information and analyze findings. Through a variety of sources, they gain a deep understanding of target sectors and results so that they can support the team to apply lessons and improve strategies.

In addition, MDF managers demonstrate key behaviors. They interact frequently with team members. They ask questions when they don’t know or don’t understand things. They admit when they have made a mistake and demonstrate what they have learned from it. They are available to talk with staff members most of the time, leaving the doors to their offices open and encouraging staff members to raise issues with them any time. Many MDF team members cite their managers’ open door policy as a key factor in the development of MDF’s culture. This openness encourages the team to express their opinions and to listen to others.

To encourage thorough gathering of information, analyzing it objectively and using it effectively, managers ask a lot of questions. The questions focus on:

- what team members are finding out in the field, through formal assessments as well as informal conversations;

- what those findings mean in terms of how a particular market system works and is changing;

- what additional information is needed to better understand the situation and interpret findings;

- how should the program react to the analysis to be more effective, for example by changing, adding or closing an intervention

- what has the team member learned.

MDF managers support the team members to improve. The managers praise team members when they demonstrate the behaviors of a learning culture, such as bringing up an idea, voicing an opinion or producing a well-thought out analysis. They point out potential problem areas and encourage more thinking on them. They also encourage and participate in reflection both when things go well and when things don’t – highlighting connections to the frameworks used to guide the program.

| Tip: Enforcing Discipline In MDF, developing a well-thought-out results chain is one of the requirements for the approval of an intervention. Connection the completion of ‘thinking’ and results measurement activities to the approval for actions ensures that these key activities are not skipped. |

At the same time, managers enforce discipline. They establish clear deadlines and expectations. They do not accept that being busy is an excuse for not following frameworks and processes or sloppy thinking. For example, all staff members must come well prepared to monthly and six monthly meetings when interventions and strategies are discussed. Managers do not allow results measurement activities to fall behind. If results measurement tasks and documents are not completed on time, they call for a results measurement ‘lock down’ week, where the whole team stays in the office to complete the tasks. MDF managers have found that discipline is a critical aspect of a learning culture. However, the necessity to frequently enforce this discipline lessens as it becomes a norm in the organization.

Establishing a constructive atmosphere

Managers are the key to establishing a constructive atmosphere in the office. The following are managers’ behaviors that the MDF team feel have contributed to the establishment of MDF’s organizational culture.

- Be available. MDF managers are available to talk with staff members most of the time. They encourage staff members to come discuss any success, challenge or issue with them at any time and they frequently circulate around the office asking staff members how their work is going.

- Be calm. When things go wrong in MDF, there is no drama. Managers encourage the calm analysis of the situation followed by determining a plan to address the problem, if possible, and pinpointing lessons learned.

- Cultivate a sense of humor. Laughing makes work more pleasant and encourages interaction. MDF managers take opportunities to make jokes and encourage humor in the workplace.

- Pay attention to motivation levels. MDF managers monitor motivation levels, both in individuals and the team as a whole. When levels drop, the managers try to find out why and address it.

- Build trust. Individual staff members and the team as a whole are more likely to learn and improve in an atmosphere where they feel they can take risks, make mistakes and improve. That atmosphere must include trust. Managers convey to staff that they are there to help.

- Be consistent. For norms to develop, the leadership must be consistent in promoting those norms. MDF managers strive to be consistent in their directions and behaviors.

- Demonstrate integrity. Even when it’s difficult, managers strive for honesty. For example, one MDF business adviser noted that when results are aggregated in preparation for reporting, any mistake found is corrected regardless of the implications for the figures. This demonstration of integrity reinforces that all MDF team members should be open about mistakes because the most important thing is to improve the program, not report particular figures.

- Have fun. MDF managers emphasize that staff members should enjoy their work. In addition, fun activities – such as celebrating birthdays and social activities after work, build relationships and improve teamwork.

Building competence over time

MDF managers emphasize that the process of building a team with the right culture and capacity takes years, not weeks or months. They aim to build the competence and confidence of team members over time. Key aspects of this process are as follows.

- Reduce guidance over time. MDF managers initially guide staff through the process of using a new framework or tool – such as the intervention guide. Over time, managers have encouraged and enabled the team to manage more of the process themselves, reducing their input to providing feedback.

- MDF managers have gradually layered on more complex aspects of market development. Initially, managers’ discussions with business advisers focused on the basics of market development – sustainable business models with pro-poor impacts. As capacity has grown, they have introduced the team to more complex concepts and frameworks. For example, this year MDF introduced a new framework to conceptualize and track systemic changes. This has enabled the team to play an increasing role in developing MDF’s strategies.

- Link information to frameworks. Managers take opportunities to point out connections to the frameworks as findings from the field come in. For example, a member of MDF’s horticulture team recently noted that a partner company that provides agricultural inputs retained all the field promoters hired with cost-sharing from MDF after support from the program ended. The Country Representative took the opportunity to link this finding to the systemic change framework reinforcing how the tool can aid in analyzing results. Click on the image to see Sangita Kumar, MDF Business Adviser, discuss MDF’s organizational culture and how managers influence it.

- Progressively hand over management roles. Initially the MDF managers fully handled all management roles. However, as capacity has grown, the managers have handed over some responsibilities. For example, after a couple of years of operating in Fiji, MDF added the position of ‘Team Coordinator’ and promoted one of the business advisers into this position. The Team Coordinator now handles an increasing share of the management responsibilities. Managers have also handed over considerable responsibility for training and mentoring new staff to the current business advisers and results measurement specialists. This approach develops local leadership and encourages the team to take increasing responsibility for building capacity.

These strategies have resulted in staff members improving the sophistication of their analysis and taking increasing initiative with management and implementation processes.

The steady progression enables MDF to improve as a whole, strengthening aspects of the program and responding to the evolving requirements of generating pro-poor systemic change.

Click on the image to see Sangita Kumar, MDF Business Adviser, discuss MDF’s organizational culture and how managers influence it.

4.2.2 Program Structure

MDF’s personnel structure and the roles and responsibilities are critical to the organizational culture. Every staff member must feel that s/he has a stake in the success of the program and can concretely contribute to that success. This means that every team member has both the opportunity and the motivation to contribute his/her ideas and opinions and to improve his/her performance. The following are key aspects of the program structure that MDF has found are important to a learning culture.

- The personnel structure is relatively flat. Initially MDF had only two types of positions – business advisers and managers. A flat structure encourages open communication among all staff and discourages vertical silos that can block the free flow of information and ideas. Even now that MDF has added additional positions, managers continue to reinforce multiple connections among the team and managers, rather than a hierarchical structure.

- Business advisers manage multiple interventions. In MDF, each business adviser manages about three interventions and also has the responsibility to look for new interventions. It is easy for people to get attached to their work and see results in a positive light. Managing multiple interventions makes it easier for a business adviser to accept when one or two are not going as well as expected. At the same time, managing multiple interventions gives business advisers the opportunity to transfer lessons from one intervention to the next.

- Each intervention is managed by two business advisers. This encourages conversation about progress and findings and reduces the risk that business advisers will become isolated. Sharing the responsibility of managing an intervention also enables business advisers to be involved in more interventions.

- Sector teams overlap. If the sector teams are discrete, they often become isolated silos. There is less potential to share lessons across the program and unhealthy competition between the teams can arise. At the same time, it is difficult for each business adviser to gain an in-depth knowledge of a sector if s/he is spread too thinly. To balance these issues, MDF has settled on a structure where the majority of a business adviser’s work is in one sector. However, several business advisers have a few responsibilities in a second sector. Others are focal persons for results measurement or cross-cutting issues such as women’s economic empowerment or the environment. This structure allows business advisers to focus but also promotes learning across the program. Click to see MDF Fiji’s organogram.

| Tip: Maintaining Objectivity

MDF managers have found that it is particularly important to look out for business advisors losing objectivity when an intervention has been going for a long time and a considerable amount of staff time and energy has gone into it. It is also important to keep an eye on objectivity when an intervention is particularly important to the portfolio and there is pressure to succeed. |

-

The sector teams are responsible for most results measurement tasks. While MDF encourages cooperation in all results measurement activities, placing the responsibility for results measurement squarely with the business advisers fosters their ownership of results analysis and encourages them to ask the results measurement team for assistance. This set up minimizes the common problem in programs whereby the results measurement team is seen as the ‘police’ or has to always hound the sector teams for information. The DCED Standard supports the involvement of the business advisors in results measurement by including staff members’ understanding and use of the system in the compliance criteria. Click to see the section of MDF’s Results Measurement Manual that details roles and responsibilities.

Despite these strategies, it is still human nature for business advisers to get attached to their interventions and become protective of them or lose objectivity. MDF managers keep an eye out for this and use the opportunity of new interventions starting or old ones finishing to shuffle management of the interventions when necessary.

Click on the image to view Mili Ratu, MDF Fiji Team Coordinator, discussion MDF’s personnel structure in Fiji and other aspects of MDF’s learning culture.

4.2.3 Physical Environment

The physical environment that people work in can strengthen or undermine a learning culture. The MDF team has found the following aspects of their physical environment help to reinforce their learning culture.

- An open office plan. MDF staff work physically close together with no partitions between them. This set up encourages conversations and teamwork.

- Convenient meeting spaces. MDF has both formal and informal meeting spaces. In addition to a large meeting room, several smaller offices are often used for small meetings. The lunch area provides a good informal meeting space. Convenient meeting spaces make it easy for business advisers to discuss and cooperate.

- Tools for visualization. The MDF office has plenty of flip charts and white boards. The team has found that visually capturing thoughts and details in meetings helps team members to communicate, participate and jointly develop ideas and plans. Visual tools are an important aspect of almost all discussions in MDF.

- All staff in one office. All MDF staff members work out of the same office in Suva. MDF has found that physical proximity is very important to cooperation and learning. Although it might be more convenient to have regional offices, this would be at the expense of the regular interaction that fosters much of the learning in MDF.

| Tip: Creating a Virtual Learning Space

While the MDF team in each country is based in one office, MDF also aims to foster learning among its country teams. To do this, MDF chose an on-line networking platform called Mango-Apps. The platform uses many of the techniques of social networking to encourage interaction among team members in different countries. For example, it is easy to share information by writing a short message after a field visit. Business advisers can achieve higher ‘levels’ by increasing their posts and accessing more information, which motivates more involvement. The platform also houses all of MDF’s documents, making information easily accessible within and across countries. While it took time and encouragement to get the staff members to use the platform regularly, now many of them follow – and learn from – interventions in other countries. |

4.2.4 Management Tools and Processes

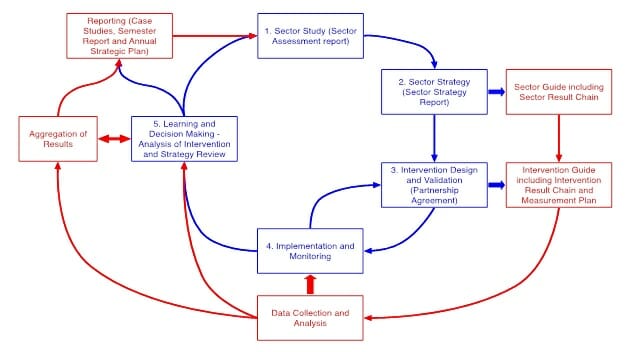

MDF has a clear set of processes that structure questioning, information gathering, analysis, planning, implementation and reflection. These are summarized in Figure 4. These processes have been central to reinforcing and structuring MDF’s learning culture (as well as its compliance with the DCED Standard). It is important that a learning culture is not just a ’talk shop’ where there are lots of discussions but analysis and ideas don’t actually feed into better implementation. MDF’s management processes impose discipline and link analysis to action, ensuring that improvements in decision-making and work with partners are fundamental parts of the learning culture.

- Focus frameworks on key questions. Frameworks and tools must focus on key questions and be structured to encourage thinking, rather than mindless filling out of forms. For example, MDF found that the format for its measurement plans has sometimes encouraged cut/paste filling out or rigid adherence to long lists of indicators, rather than critical thinking on how to measure an intervention effectively. So, the team has adjusted the format and reinforced the collaborative process for developing the measurement plan with the aim of making it a tool for thinking about how to appropriately measure the progress and results of an intervention, rather than a form to be completed. (Click for MDF’s measurement plan format.)

- Make frameworks visual. Diagrams, flow charts, time-lines and tables can all help staff members to understand and apply frameworks more effectively. MDF has found that visually capturing concepts helps team members to communicate with each other more clearly and develop ideas more thoroughly.

- Apply frameworks robustly. It is important to ensure that the tools and processes are applied robustly. This does not mean rigid adherence to procedures but rather ensuring quality in the application of tools. To ensure quality, managers and team members discuss and challenge each other, making the group’s thinking more thorough and clear. The DCED Standard framework helps the team to ensure adequate quality in all aspects of the system.

- Integrate key cross-cutting issues into frameworks. Those issues that are critical to the program must be thoroughly integrated into the frameworks and management processes. For example, over the last year, MDF has taken steps to more thoroughly integrate women’s economic empowerment into its management processes in order to further develop implementation in this area.

- Don’t treat frameworks as the goal. While the frameworks and processes are important, they should not become an end in themselves, but rather a means to think, discuss, plan and improve performance. MDF has found that, at times, even the best frameworks can create confusion or get business advisers stuck. In these cases, the managers have temporarily parked the frameworks and focused in on key questions that the frameworks aim to address.

-

Evolve frameworks over time. Frameworks and management processes must evolve as new learning is gained, the team grows in capability and the needs of the program change. Frameworks are used to make sense of information from the field. But sometimes analysis of information from the field shows that a framework needs to change to better capture the field reality. MDF has found that frameworks can guide learning but must also evolve in response to learning. Frameworks must be simple enough to be understandable and yet complex enough to be useful.This balance changes with time as the team becomes more familiar with the target markets and with the frameworks themselves. Over time, MDF has introduced more complexity into its frameworks in response to learning, increased capacity and changing needs of the program. For example, the focus on systemic change has increased as the team gains a more sophisticated understanding of target markets and the potential for changes to become more systemic increases.

External Influences on MDF’s Culture

Three factors, external to a program, affect the organizational culture: program design, donor and stakeholder support and the culture of the country. MDF’s experience with each is discussed below.

Program design

MDF has a program design that supports a learning culture and MDF’s focus on constantly improving performance. The key elements of the design in this respect are outlined below.

- Flexibility: flexibility is key to improving performance. If a program does not have some flexibility in implementation, then there is no way to improve. Thus, even if staff members learn, they have no scope to make better decisions. While the MDF design specifies high-level objectives, it gives the implementing organization considerable flexibility on ways in which to pursue those objectives, emphasizing the process for decision-making rather than specifying the actual decisions.

- Implementation, not execution: a program design must put the contractor/grantee in the role of implementer, with the mandate to maximize results with the time and money available. A program design is based on a limited investigation, generally at one point in time and using the best available information at that time. A program team is able to gain new insights into the economy and target sectors as the program progresses. The team is able to devise ways to improve performance based both on their own experience and advances in the wider field. If the design puts the contractor or grantee in the role of executing a pre-planned set of activities, there is no room to use new insights gained. MDF’s design specifies that the contractor is expected to learn and improve strategies throughout the program. It also specifies that the programme should use the DCED Standard, to ensure that it regularly gathers credible information on results to inform improvements.

It is also critical that a program can request changes to a design when necessary. This allows the program to use new insights to improve not just implementation, but the design of the program. For example, in consultation with DFAT, MDF has changed the personnel complement and structure of the program to meet both unanticipated and changing needs in implementation. MDF has found that when aspects of the program design do not work as well as they might, it is better to bring it up with DFAT and discuss changes, rather than try to make do with the original design.

Donor/stakeholder support

A program’s donor(s) and other stakeholders can have a significant influence on the organizational culture.. In the MDF design, DFAT emphasized that compliance with the DCED Standard was not just for reporting but also to support learning and improvement in both the program and the agency. This expectation set the stage for the development of an effective learning culture. It also encouraged discipline and provided for resources for results measurement and learning in the program.

However, MDF emphasizes that a donor’s support for program flexibility should not just be expected or demanded. It must be earned, through regular communication and relationship building. Some of the strategies that MDF has used to encourage DFAT’s support of its focus on learning and improving are listed below.

- Provide frequent updates. MDF regularly explains to DFAT managers, the processes it is going through, and progress in learning and improving – as well as results.

- Share the learning process. MDF incorporates DFAT into its learning culture. MDF managers offer DFAT officers as many opportunities as possible to visit and get to know the program. MDF managers discuss problems and learning with the DFAT personnel assigned to managed MDF, providing the opportunity for DFAT to input into the learning process in the program.

Click on the image to see Malcolm Bossley, DFAT Senior Program Manager, discuss his perspective on MDF and its culture.

- Encourage the staff to interact with the donor. MDF managers gradually encourage the staff to attend and make presentations when DFAT personnel visit. The managers provide support beforehand, explaining what sorts of questions and issues may come up and encouraging open discussion. That way the relationship between the program and the donor is deeper than just at the managerial level. At the same time, should friction arise that may discourage staff from taking risks and learning, MDF managers move to address the issue directly with DFAT personnel. MDF has a positive and productive relationship with its donor, a result of good faith and an effort to build an open relationship on the part of both parties.

Country culture

Every culture has aspects that support learning in a work setting and aspects that stifle it. The trick is to build on the supporting aspects and persevere in gradually addressing the stifling aspects. Hofstede’s framework for categorizing national cultures according to six dimensions is useful in considering how national culture impacts on organizational culture. Below, two of Hofstede’s dimensions – Power Distance and Individualism – are used as examples to show how MDF took Fiji’s culture into account in its efforts to develop learning norms in the program. Click on the image to see Malcom Bossley, DFAT Senior Program Manager discuss his perspective on MDF and its culture.

‘Power Distance is defined as the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally’ (The Hofstede Centre). Fiji’s score on this dimension indicates that it is a hierarchical society. People generally accept a hierarchical order and in the workplace subordinates expect to be told what to do (The Hofstede Centre). In this culture, MDF managers had to work hard to break down any perceived hierarchies in the office, for example based on age or qualifications. They had to ensure that everyone felt comfortable voicing their opinion and that everyone listened to others’ opinions. This was partly addressed through recruitment but constant reinforcement is always necessary.

‘Individualism is the degree of interdependence a society maintains among its members.’ (The Hofstede Centre) Based on this dimension, Fiji is considered a collectivist society, where relationships are critical and people value their membership of groups (The Hofstede Centre). This characteristic of Fiji’s culture supports teamwork and the value of working together to advance MDF’s goals. MDF has built on this aspect of Fiji’s culture – encouraging strong relationships among the team and using group work as a key learning mechanism.

In each country where it works, MDF managers have to study the national culture, understanding how it supports learning and how it does not. This helps them to determine the most effective ways to promote a learning culture.

Click on the image to view Harald Bekkers, MDF Team Leader, discuss key aspects of, and influences on a program’s learning culture.

The Benefits of a Learning Culture

In his paper, ‘Best Practices in Results-Based Management – A Review of Experience,’ John Mayne discusses appropriate incentives for results-based management. He states, ’In results management, the aim is to have individuals and units deliberately plan for results and then monitor what results are actually being achieved in order to adjust activities and outputs to perform better.’ (Mayne, J. (2007) ‘Best Practices in Results-Based Management: A Review of Experience’ for the United Nations Secretariat. Volume 2: Annexes, p. 34) Indeed this is the aim of a learning culture. The pay-off of having a learning culture in a program is systematically maximizing long-term and sustainable results within the time and resources available.

There are other benefits of a learning culture as well. It helps programs to recruit and retain the right kind of staff – bright, analytical people with a hunger to improve their work and the results of it. A learning culture motivates staff members by giving them the freedom, the support and the responsibility to analyse, innovate, learn and improve as a team. MDF team members say that work in MDF is both interesting and enjoyable, largely as a result of the organizational culture.

Click on the image to see MDF staff and their donor answer the question, ‘What do you like best about working with MDF’?

Acknowledgements